Lost Media Found: Reverse Engineering the Wii Fit Body Check Channel

The Nintendo Wii was a very polarizing video game console due to the fact that it catered to the casual audience. From games like Wii Sports to Wii Party, the Wii series of games were specifically made for those who had no prior gaming experience. One of these games is Wii Fit (Plus).

|

|---|

| Not actually Wii Fit, rather Wii Fit U, its successor but it is more or less the same. |

Released in 2007, Wii Fit is an exercise game featuring yoga, strength training, aerobics and balance mini-games, controlled with the proprietary peripheral, the Wii Balance Board. The game’s designer Hiroshi Matsunaga, claims the game is a “way to help get families exercising together”. Fast forward to 2009, Nintendo developed a Japanese only companion software to Wii Fit, the Wii Fit Body Check Channel.

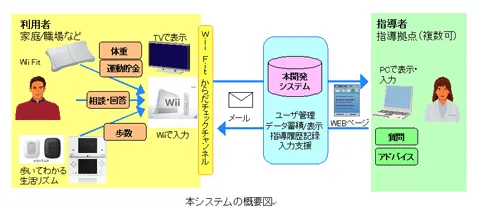

Nintendo claimed that this channel would send Wii Fit user data + pedometer data from the DS title “Personal Trainer: Walking DS” to medical professionals which would then give you health advice as well as provide them with research data. The channel was only released to companies NEC, Panasonic and Hitachi. According to Eurogamer:

NEC will use the Wii Fit Body Check Channel to get employees and their families fit and healthy; Panasonic will cater to insurance companies and health organizations; and Hitachi has a secret internal project in testing.

|

|---|

| Diagram of how the Wii Fit Body Check Channel would work. |

It would seem that this channel was never released to the public, or any further data concerning it. The only reason the software was found was because someone scraped Nintendo’s Wii Shop Channel CDN and discovered it. It was discovered that the software requires a “registration SD Card” to register a Mii (user) to the channel. An SD Card such as this has never surfaced, making it believed that this software is forever lost media.

In late July 2024, Luna Caoimhe, a member of my project WiiLink, decided to blindly translate the channel. When they finished, I became intrigued in figuring out what was on the SD Card in hopes of reviving this channel.

The Process

There are three major tools I use when reverse engineering Wii software, and this is no different.

- Ghidra Decompiler

- Dolphin Emulator

- Hex Fiend (or any hex editor)

First step was to generate a symbol map of known functions for this software using Dolphin Emulator. Dolphin has a powerful debugger which is invaluable for reverse engineering as it offers features such as memory search, memory and instruction breakpoints, as well as a log for all system functions.

NOTE: Symbol map does not set variable names. Those had to be figured out through analyzing the flow.

Next I loaded the Wii Fit Body Check Channel executable into Ghidra with the generated symbol map. I knew that the software was expecting to read a file on the SD Card, so I went through the registration process in the software in order for the logs to tell me where it is reading data into. This turned out to be memory address 0x804d34a0.

Core/IOS/SDIO/SDIOSlot0.cpp:280 I[IOS_SD]: DMA Read 1 Block(s) from 0x00000000 bsize 512 into 0x804d34a0!

By setting a memory breakpoint on 0x804d34a0 , I was lead to a function at 0x8018c45c which involved reading data into a buffer. Back in Ghidra, I was able to follow the functions that reference this function until I found a snprintf function with a string that contains directories typically found on an SD Card written by the Wii.

This file was discovered to be at the path /private/wii/app/HFNJ/user.fdu.

To figure out what processes the file, I first created a file with that path and filled it with junk data I can search for in memory. This time I performed a read only memory breakpoint on 0x804d34a0, which lead me to a function at 0x802eca48 . Let’s call this DecryptRegistrationData as later we discover that is what the function does. The first observation I made was this if statement:

char* file_data;

size_t file_size;

if ((file_size < 28) ||

(iVar3 = MSL_C.PPCEABI.bare.H::memcmp(file_data,s_Yos3_8039a760,4), iVar3 != 0)) {

return 0;

}

This tells me two things:

- The file size must be greater than 28 bytes

- The first four bytes must be equal to the string literal “Yos3”

The return code of 0 however confused me as that typically signifies success. Checking the caller, I saw that it performs a countLeadingZeros instruction on the result. Specifically:

res = DecryptRegistrationData(ctx->decrypted, 328, ctx->file_data, ctx->file_size);

uVar1 = countLeadingZeros(res - 328);

if (uVar1 >> 5 == 0) {

iVar8 = 3;

}

if (iVar8 != 2) {

// Error flag is set here

}

The bit size of uVar1 is 32 as it is an unsigned 32-bit integer. The only value of uVar1 that fulfills uVar1 >> 5 == 0 is 32. countLeadingZeros can only return 32 if the argument is 0. Therefore the return value of DecryptRegistrationData must be 328.

Returning to DecryptRegistrationData:

char buf[20];

char* file_data;

zz_802ed660(buf, file_data + 24);

// The code doesn't actually call memcmp although it really should...

// Instead it manually compares the bytes in buf and file_data

if (MSL_C.PPCEABI.bare.H::memcmp(file_data + 4, buf , 20) != 0) {

return 0;

}

Based on previous experiences and knowledge of various hashes, I hypothesized that zz_802ed660 was a function to calculate the MD5 hash of the data as the size of buf is 20, the exact size of the MD5 hash. I was able to verify this by performing an instruction breakpoint on the instruction after zz_802ed660 and inspecting the value of buf, then comparing it with the MD5 sum I calculated.

Next, the function reads the next 8 bytes into two unsigned 32-bit variables. It then reads every byte sequentially. The first integer is unknown for now while the second is the encrypted file size. The latter is also the value which is returned on success, meaning that is must be equal to 328 as established above.

int uVar5 = 0;

int uVar2 = 0;

int uVar6 = 0;

int curr_offset = 0x1c

DAT_8059aac8 = (uint)file_data + 20;

int uVar4 = (uint)file_data + 24;

while (uVar5 < uVar4) {

// Process data

// Stay inbounds

if (file_size <= curr_offset) {

return 0;

}

if (uVar2 == 0) {

uVar6 = (uint)*(byte *)((int)file_data + curr_offset);

uVar2 = 128;

curr_offset = curr_offset + 1;

}

if ((uVar6 & uVar2) == 0) {

// Process two bytes

} else {

// Process single byte

}

uVar2 = uVar2 >> 1;

}

To keep things simple, I opted to only process a single byte in my implementation. In order to do this, uVar6 & uVar2 must always be equal to 0. This can be achieved by setting every eighth byte to 255 (unsigned 8-bit integer maximum). The sequence is due to the fact that uVar2 >>= 1 will become 0 after 8 iterations which is reset once uVar = 128.

Finally, we deal with the encryption.

// Process single byte

char* file_data;

DAT_8059aac8 = DAT_8059aac8 * 0x19660d + 0x3c6ef35f;

byte data = *(byte *)(file_data + curr_offset);

curr_offset = curr_offset + 1;

decrypted_data = data ^ (byte)(DAT_8059aac8 >> 0xc);

uVar5 = uVar5 + 1;

Upon inspection, it would seem that the encryption is a simple XOR cipher. DAT_8059aac8 is the seed in a linear congruential generator, which is used to encrypt the data.

With DecryptRegistrationData fully decompiled, I returned to the caller function. Upon returning, I saw a function that I have seen countless times in Nintendo’s binary files; the CRC32 checksum calculator.

iVar5 = OSCalcCRC32(¶m_1->decrypted_data + 4, 324);

uVar1 = countLeadingZeros(iVar5 - ctx->decrypted_data->crc32);

Analyzing the flow shows that the first 4 bytes of the decrypted data is the CRC32 checksum of the rest of the decrypted data.

The rest of the code was straight forward.

countLeadingZeros(ctx->decrypted_data->zero)

The value after the CRC32 checksum must be zero. The following data were all strings. There was a wcslen function and a strlen function which then copied the string into its own respective buffer.

Without testing, it can be deduced that the wide string is the instructor name and the 8-bit string is the instructor email. This is because RFC 5322 states that an email address may only have ASCII characters.

After testing however, it was determined that the max string lengths are 12 and 296 respectively.

Creating an implementation

With the entire file figured out, I could now generate my own. I opted for the Go programming language as it is exceptional at generating binary files.

First was forming a binary structure:

type WiiFitData struct {

CRC32 uint32

_ uint32

InstructorName [12]uint16

InstructorEmail [296]uint8

}

Next was creating a linear congruential generator:

type random struct {

seed uint32

}

func (r *random) randomNumberGen() uint8 {

r.seed = r.seed*0x19660d + 0x3c6ef35f

return uint8(r.seed >> 0xc)

}

We shift the result by 12 as that is what the decryption function does in the binary.

Finally, encrypt the data after we populate it.

seed := 10

r := random{seed: seed}

temp := new(bytes.Buffer)

err := binary.Write(temp, binary.BigEndian, uint32(328))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to write decrypted data size")

}

err = binary.Write(temp, binary.BigEndian, seed)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to write seed")

}

decrypted := makeUnencryptedData()

status := 0

for i := 0; i < len(decrypted); i++ {

if status == 0 {

temp.WriteByte(255)

status = 128

// Retain position in decrypted slice.

i--

continue

}

// Perform the encryption.

temp.WriteByte(decrypted[i] ^ r.randomNumberGen())

status >>= 1

}

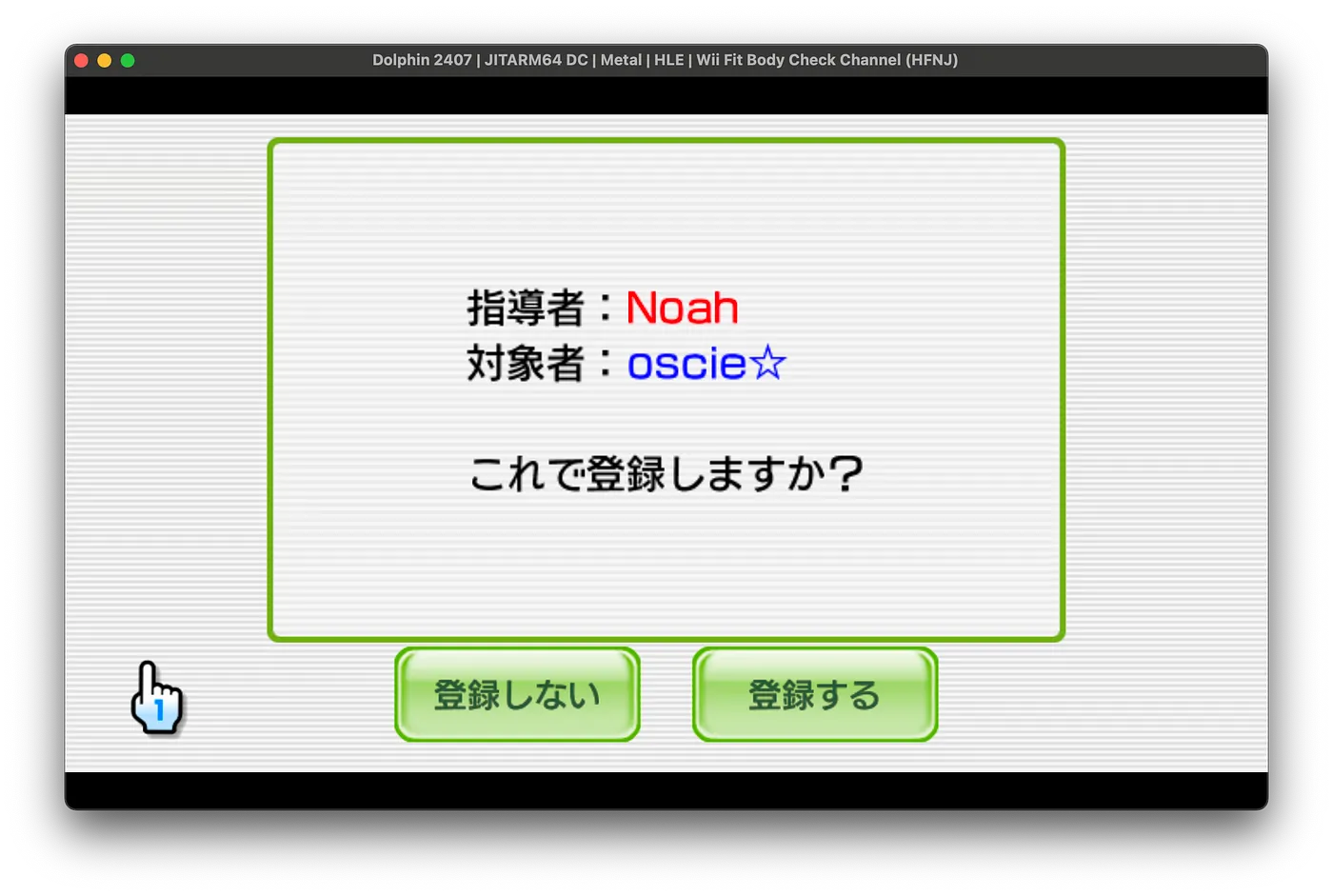

Once compiled, I take the outputted data and insert it in the correct path on the SD Card. Upon testing, I was able to register a friend’s Wii Fit save file to me as an instructor. The registration process uses the Wii’s Mail service to interact with the instructor. As my project revived that service, the mail aspect is functional.

|

|---|

| Registration screen for the Wii Fit Body Check Channel |

Final Thoughts

This was an extremely rewarding challenge for me as it tested my knowledge on the Wii system, byte operations and my problem solving abilities. Additionally, it tested how effectively I am able to leverage the tools at my disposal.

The main challenge came from the fact that I did not have any source files to reference for this, meaning everything was completely done from scratch. This however only strengthened my problem solving skills as it is drastically different from the other pieces of software I reverse engineer.

I am excited to continue looking into this channel as the hard part is now complete. I am now awaiting a copy for Personal Trainer: Walking to ship in order to discover what else this channel has to offer.

You can see the full code here on my Github repository.